Tao Te Ching “Tao Te Ching” was written by Lao-tzu around the 6th century BC. “Tao” means the way of all life, This term, which was variously used by other Chinese philosophers, including Confucius, Mencius, Mozi, and Hanfeizi, has special meaning within the context of Taoism, where it implies the essential, unnamable process of the universe. “Te” basically means “virtue” in the sense of “personal character”, “inner strength”, or “integrity”. “Ching” refers to classic or canon.

|

|

“Tao Te Ching” is a short text of around 5,000 Chinese characters in 81 brief chapters. The topics range from political advices for rulers to practical wisdom for people. There are some evidences that the chapter divisions were later additions for commentary, or as aids to rote memorization, and that the original text was more fluidly organized. It has two parts, the Tao Ching from Chapter 1 to 37 and the Te Ching from Chapter 38 to 81. The ideas are singular and the style poetic. The written style is laconic, has few grammatical particles, and encourages varied, even contradictory interpretations. “The Way that can be told of is not an unvarying way. The names that can be named are not unvarying names.” These famous first lines of the Tao Te Ching state that the Tao is ineffable, nameless, going beyond distinctions, and transcending language. In Lao-tzu's Qingjing Jing he clarified the term Tao was nominated as he was trying to describe a state of existence before it happened and before time or space. Way or path happened to be the side meaning of Tao, ineffability would be just poetic. This is the Chinese creation myth from the primordial Tao.

“It was when intelligence and knowledge appeared that the Great Artifice began.”“The pursuit of learning is to increase day after day and the pursuit of Tao is to decrease day after day.” The Tao Te Ching praises self-gained knowledge with emphasis on that knowledge being gained with humility. When what one person has experienced is put into words and transmitted to others, so doing risks giving unwarranted status to what inevitably must have had a subjective tinge. Moreover, it will be subjected to another layer of interpretation and subjectivity when read and learned by others. This kind of knowledge, like desire, should be diminished.

“Tao Te Ching” was a suite of variations on the “Powers of Nothingness”. This resonates with the Buddhist Shunyata philosophy of “form is emptiness, emptiness is form”. Emptiness can mean having no fixed preconceptions, preferences, intentions, or agenda. “The Sage has no heart of his own. He uses the heart of the people as his heart.”From a ruler's point of view, it is a laissez-faire approach. Looking at a traditional Chinese Landscape, one can understand how emptiness and the unpainted have the power of animating the trees, mountains, and rivers it surrounds.

Another theme of “Tao Te Ching” is the eternal return. There is a contrast between the rigidity of death and the weakness of life. “When he is born, man is soft and weak; in death he becomes stiff and hard. The ten thousand creatures and all plants and trees while they are alive are supple and soft, but when dead they become brittle and dry.” This is returning to the beginning of things, or to one's own childhood.

The “Tao Te Ching” focuses upon the beginnings of society, and describes a golden age in the past. Human problems arose from the “invention” of culture and civilization. In this idealized past, “the people should have no use for any form of writing save knotted ropes, should be contented with their food, pleased with their clothing, satisfied with their homes, should take pleasure in their rustic tasks”.

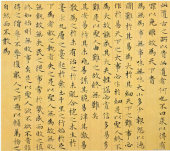

“Tao Te Ching” contains a good summary of different calligraphies. The Chinese characters in the original versions were probably written in Zhuan Shu (seal script), while later versions were written in Li Shu (clerical script) and Kai Shu (regular script) styles.

|